By Aadielah Maker Diedericks, Makhosazana Ndlovu, Julian Jacobs

In a country grappling with one of the highest alcohol consumption rates per drinker in the world, South Africa cannot afford regulatory silence. Yet, nearly a decade after it was introduced, the Liquor Amendment Bill of 2016—designed to tackle alcohol-related harm—remains in legislative limbo. The reason, as revealed in recent research, is deeply troubling: the liquor industry has effectively captured a key policymaking forum, the National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC).

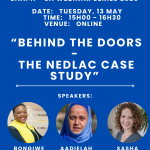

The Southern African Alcohol Policy Alliance (SAAPA), in collaboration with the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), Wits University, and the University of Stirling, recently hosted a webinar presenting new findings on why the Bill has stalled. The results, drawn from detailed document analysis of NEDLAC minutes and documents obtained through the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) requests, paint a picture of regulatory capture, skewed representation, and a lack of transparency at the very heart of policy negotiation.

At the launch, SAAPA Chairperson and Hlanganisa SA Community Fund CEO, Bongiwe Ndondo, laid the foundation for why this issue extends beyond health. “We are facing a health crisis, a socio-economic crisis, and a social justice crisis,” she said. “Those at the bottom of our society are disproportionately impacted by the harms of alcohol.” These harms include road deaths, gender-based violence, cancer, and a host of other public health burdens—often affecting communities already facing systemic inequality.

The Liquor Amendment Bill was developed to address some of these problems. Its provisions were aligned with World Health Organization (WHO) best buys – reducing availability, restricting marketing and increasing the price – and included raising the drinking age from 18 to 21, restricting alcohol advertising (particularly on social media), enforcing a 500-metre trading radius from schools and religious sites, and introducing a liability clause to hold producers accountable when their products fuel unlicensed or harmful consumption and results in harm.

Despite widespread public consultations in 2016 and supportive findings from both government and even industry-commissioned socio-economic assessments, the Bill failed to progress. Researcher Aadielah Diedericks, who helped lead the investigation into NEDLAC, explained why. Using PAIA, the team sought access to liquor-related meeting minutes between 2016 and 2022. Upon receiving documents, they discovered that meeting records of 2018 and 2019 were not included. Another PAIA request resulted in no additional documents.

What they discovered was alarming: the imbalance in stakeholder representation. The study found that fourteen alcohol industry organisations—including giants like AB InBev, Diageo, Heineken, and Distell—dominated five liquor-related structures within NEDLAC’s Development Chamber. These organisations were not passive attendees; they actively shaped discussions through sub-committees, trade associations like the Beer Association of South Africa (BASA), the National Liquor Traders Association (NLTA), and the South African Liquor Brand Owners Association (SALBA), and larger business groups such as Business Unity South Africa (BUSA) and Agbiz.

Meanwhile, the community and development sector presence in these deliberations was sparse to non-existent. As Diedericks pointed out, “The industry was not only present—they were structured, strategic, and had a sustained voice. Civil society simply wasn’t at the table.”

This lack of balance matters. It means the people most affected by alcohol harm—community members, healthcare workers, and social justice advocates—had no meaningful say in how the laws governing alcohol sales and marketing were shaped. The consequences of this exclusion are not hypothetical. While industry players argued for voluntary self-regulation, the research reveals that these mechanisms are not only ineffective but compromised.

Take, for example, the industry-led awareness body, AWARE. Though positioned as a public education platform, AWARE is governed and funded by the very industry it claims to hold accountable. Minutes from NEDLAC meetings in 2020 reveal how financial control by the industry over such campaigns undermines the independence of public health messaging. AWARE’s CEO and board are industry-appointed, which raises red flags about its credibility and public accountability.

Even when the government attempted to support its policy recommendations with evidence, industry pushback prevailed. Notably, Genesis Analytics—a consultancy commissioned by the liquor industry itself—found in 2017 that the Liquor Amendment Bill could reduce alcohol consumption and save lives. That report, too, was dismissed and buried.

Human rights lawyer and Section27 Executive Director Sasha Stevenson warns that this is part of a broader pattern. “We see policies that come close to being implemented and then go nowhere,” she said. Stevenson points out that this resistance to regulation is not unique to the alcohol sector. Similar tactics have been used to delay or derail health-related policies such as the Health Promotion Levy (sugar tax) and front-of-pack warning labels on processed food.

Stevenson underscored the constitutional stakes: “The right to healthcare includes preventative measures. This is not optional. Participation in policy spaces must be more than symbolic—it must include those who bear the brunt of harm.” She also called for civil society to organise more effectively, ensuring its representation is not only louder but structured and sustained.

The research calls for a complete overhaul of how NEDLAC functions. That includes implementing a rigorous conflict-of-interest policy, ensuring meaningful and elected, not appointed, representation from affected communities, and reviewing the structure of its Community and Development Chamber.

What’s at stake here is not just one piece of legislation—it’s the integrity of South Africa’s democratic processes. PAIA, which is supposed to promote transparency, is being weaponised to obscure critical policy debates. And without urgent reforms, public health will remain hostage to private business interests.

This moment is an opportunity. Government, in partnership with civil society, researchers, and rights-based organisations, must seize it, not just to revive the Liquor Amendment Bill, but to reclaim policy-making spaces that have long been dominated by profit-driven voices.

Because when policy is made behind closed doors, it is the public who pays the price.